These original subjects are now between 52 and 58 years old. Most of the children who did not hold out for 10 minutes ate the treat within six minutes.

The new study - conducted by Mischel (now at Columbia University) and colleagues around the country - suggests that focus has payed off.Īmong the 165 children who participated in the first round of experiments at Stanford from 1965 to 1969, the task tended to be either very hard or pretty easy: close to 30% gobbled up the single treat within 30 seconds of the researchers’ departure from the room, while just over 30% were able to wait the 10 minutes that was the outer limit of the researcher’s absence. The results focused psychologists, early-childhood educators and parents on the key role that self-regulation and executive function can play in a child’s prospects, and on the need to nurture those skills well before kindergarten. Other studies found that children unable to defer gratification were more likely to be become overweight or obese 30 years later and were in worse general health in adulthood. Compared to kids who lunged for the early reward, those who held out for a bigger prize did better in school, got higher SAT scores, had higher self-esteem and better emotional coping skills, and were less likely to abuse drugs.

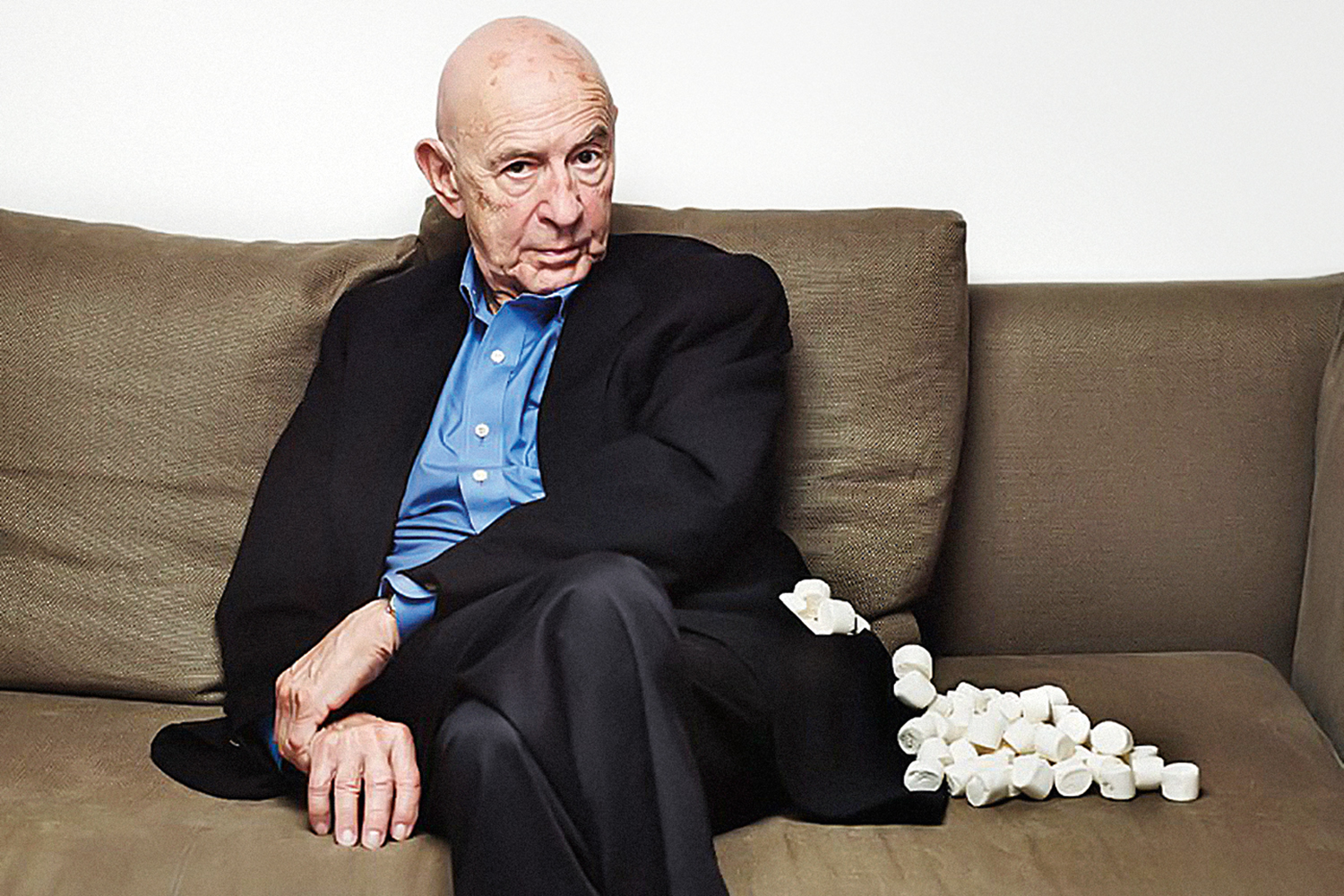

Replicated many times and followed up by a wide range of researchers, the marshmallow test has earned recognition as a powerful predictor of future performance - at least among the white children of well-educated parents. But if the child could wait for him to return before eating it, the researcher added, she could have the second, bigger treat instead.Īfter the experimenter closed the door on the subject, researchers on the other side of a two-way mirror monitored the child’s bout with temptation and recorded how long he or she could hold out before licking or eating the treat. Before leaving the room “to do some work,” the adult researcher instructed the child that the single treat on one plate could be eaten at any time. Pioneered in the 1960s by a young Stanford psychology professor named Walter Mischel, the marshmallow test left a child between the ages of 3 and 5 alone in a room with two identical plates, each containing different quantities of marshmallows, pretzels, cookies or another delicious treat. The study, published this week in the journal Developmental Psychology, resurrected an experiment that’s become a developmental psychology classic: the so-called marshmallow test. Those findings emerge from a new effort to understand how children’s ability to hold out for the promise of more has changed over time.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)